When I was younger and didn't have the finances to race real cars, I raced radio controlled cars instead. Specifically, I raced electric 1/10th-scale touring cars on outdoor asphalt with rubber tires (they were also raced indoors on carpet with foam tires). The cars were highly adjustable, even down to things we cannot realistically change on production cars, such as wheelbase, camber link length and pickup locations, damper inclination and location, and on-the-fly damper re-valving (via piston sizes and shock fluid weights). To me, one of the great things about r/c cars is that the setup knowledge can easily transfer to a real race car, since the 1/10th-scale car is governed by the same physics as the full-scale.

I will always remember what one of our local hot-shoe drivers used to say after giving a piece of advise about car setup: "Sometimes, the opposite is true." To give some context, he may have suggested something along the lines of going with softer springs up front to increase front-end grip, but he would caveat the suggestion with his catch phrase to remind you that sometimes you might actually gain front-end with a stiffer spring, rather than going softer.

I've been giving a lot of thought to car setup lately, as myself and a couple of friends are exploring aero setups for the first time, and things haven't always panned out the way we expected them to.

So how could a softer spring and a stiffer spring both potentially achieve the same desired outcome of increasing front-end grip? Let's explore this idea together.

We all know that stock suspension setups on production cars are too soft for racing and track use, but did you know that the suspension can be too stiff as well?

Ultimately, everything we do with chassis setup, alignment, tire pressure, and aero packages all have the same end goal: to achieve the maximum grip potential allowed by all 4 tires on the car.

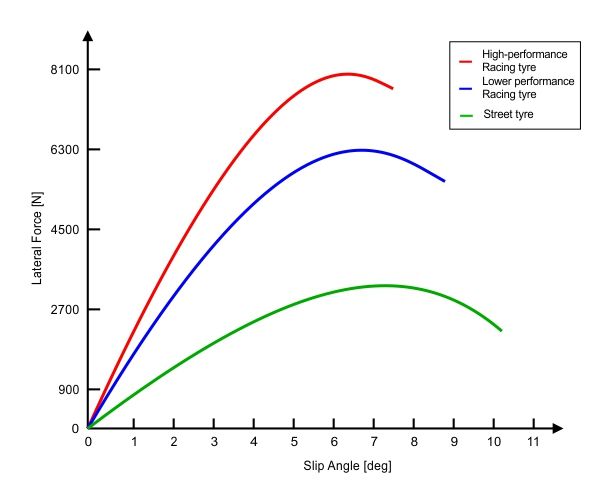

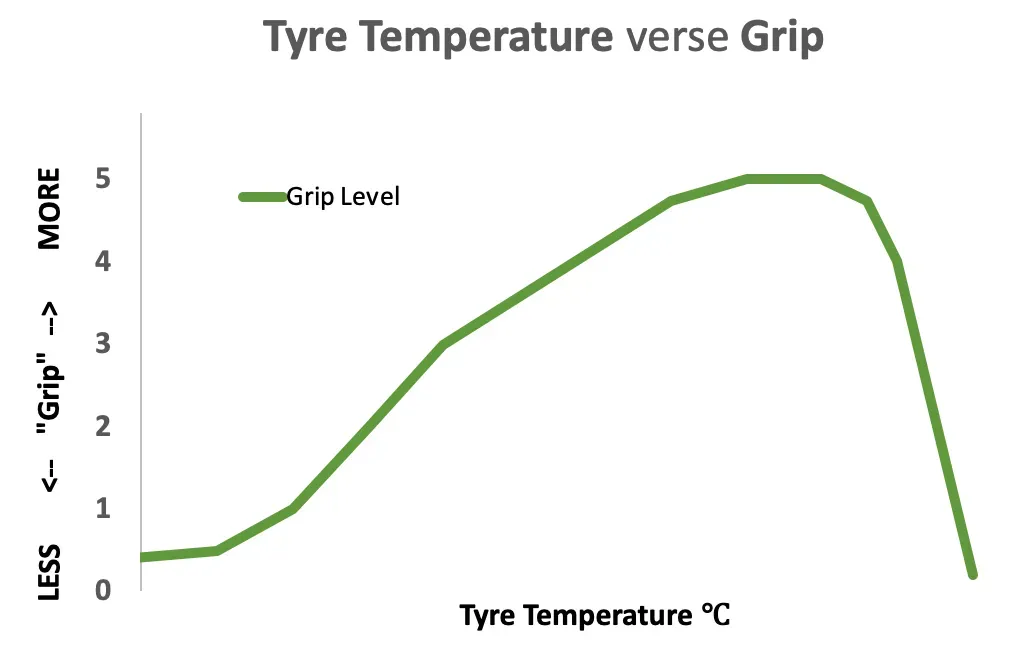

What we tend to forget is that the grip potential of a tire is shaped sort of like a bell curve. It ramps up, has a peak, and then ramps back down. That is to say: you can over-work and exceed the grip of the tire, and the grip will fall off. This will be obvious when you over-cook a corner entry, or get on the gas too early and induce a power-slide.

It isn't as obvious when your car feels pretty balanced and drives well, and you are generally in control, even though you are actually above or below the grip limit of the tire.

Let's illustrate with a common scenario: the car is understeering, and we want a more neutral car that rotates better. We could take grip away from the back end, but we are choosing to work on the end that has the issue, so we want to add grip to the front.

It would make sense to soften the front of the car, either with a damper change, softer springs, or a softer anti-roll bar setting.

If the tire is still climbing the left side of the tire grip potential bell curve, then this softer setup change should work, as the increased weight transfer will help move the tire further along the curve, closer towards the peak grip potential.

However, and this is very important to understand: if the tire is already being overworked and exceeding the grip peak, then the correct change would be to stiffen the front of the car. This would move the tire backwards on the bell curve, bringing it back into the peak zone, rather than exceeding it.

This is can be a hard concept to grasp, because our tendency is to want to soften one end of the car when we are experiencing a handling imbalance, such as extreme understeer or oversteer. After all, why would want to take traction away with a stiffer car? It seems like it would make more sense to soften the car and add grip to have the fastest possible car, but that may not be the case.

The catch is that if you have already exceeded the grip potential of the tire, you will actually be increasing grip by stiffening the car, since the decrease in weight transfer will move the tires backwards on the grip bell curve and be closer to the desired peak zone.

So how do you know where your tire is on this graph? Well, it's not easy to know with any certainty, but you can use data, testing, and intuition to make an educated guess.

It isn't always easy to tell from the cockpit of the car, especially when racing tires tend to have little-if-any audible feedback at the limit. You should be able to tell, though, if the car feels like it's leaning or pitching an excessive amount, or if its so stiff that it feels like its skipping or bouncing across the surface of the track.

You can ask around and do some online research of common setups for your chassis. Look for overall trends and see how your setup compares: is it noticeably softer or stiffer than other common setups?

How are your tire pressures and temperatures? A tire that is gaining more than 6 or 7 psi hot versus it's cold reading, or has extreme temperatures (like over 200*F) is a sign that it is being overworked.

Check out the photos that the track photographer took of your car, or try to attain in-car video footage from a car that was following you on track. Ask the driver that was following you if he noticed anything about your car. Is it lifting an inside tire? Does the car go through corners with a lot of yaw angle? Does it look like it's bouncing a lot?

These clues can all lead you to an informed decision on which direction to take your suspension setup.

Never discount your gut instinct on what the car needs, either. I tend to like a car that is slightly on the stiffer side, as I like the responsiveness and sharp steering feel, but I will also align the car to allow it to be neutral-to-understeer prone so that I can drive it hard and with confidence.

Remember that the fastest setup is going to be the one that you can confidently drive the hardest and most consistently. The setup could be quite a bit different than what the winning car in your class is running, because we all have different preferences, comfort levels, and skill levels.

I have two track E30s that both have similar spring rates, but they both feel quite a bit different on the track. I have not yet decided which I like better, because I have a lot less seat time in one of them than the other. The surprising thing is that though the spring rates are within 100lb/in of each other on both ends, the cars feel totally different due to the different dampers on the cars, and the different philosophies they are setup under for classing reasons.

The first E30 has a stock body and quite a bit of ballast to fit into TT6. It has a solid but outdated suspension: Bilstein Group N coilovers, which are linearly valved. The car was undoubtedly over-sprung before adding in the ballast, but with about 250 extra pounds in the car, it feels great now. With the better weight distribution from the ballast and the tires being better situated on the grip potential bell curve, I've actually gone faster in this car with the added weight than I did on the previous lighter setup.

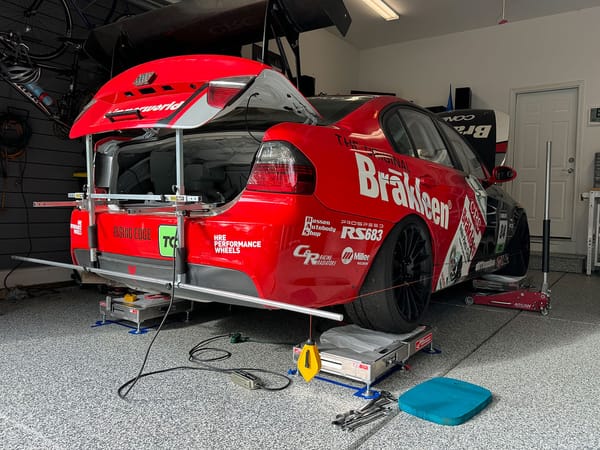

The second E30 has a full aero package that makes several hundred pounds of downforce, but runs at about the same weight and with the same tires as the first car. It has a more modern digressive AST damper package that does a great job of feeling supple and compliant when hitting curbs and bumps (high speed damping), but maintaining control in the corners (low speed damping). I am still working on getting this car to rotate better at lower speeds, but the high speed stability from the aero package is a very welcome addition to the platform.

Ultimately I expect the setups of the two cars to diverge some, as aero cars typically need to be stiffer to some degree to compensate for the added downforce, but it's interesting to be able to compare and contrast these cars, and to see what knowledge can transfer between each.

Hopefully this article gives you some food for thought with your own track car.

We're closing in on the one-year anniversary of RISING EDGE. In the coming weeks, I'm going to give away some gift cards or prizes randomly to subscribers on the email list. It is free to subscribe, and it shows me that there is a growing interest in the site and what I'm writing about.

While the site has grown quite a bit in the first year, it is still fairly small. It would mean a lot if you told a friend about the site and encouraged them to subscribe. Picking up new readers and hearing feedback helps me know the articles are on the right track and that they are helping someone out there.

Thank you for reading, and be well,

T.J.